Mallory Miles

Tree Rings

PATERNAL

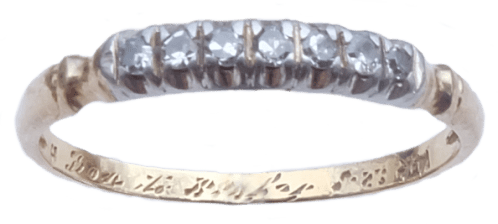

Velma, 1925. My great-great-grandmother wore a ring with seven dainty diamonds. She was a beauty queen, married at nineteen to a coal miner. They lived in a narrow white house identical to all the other narrow white houses in the company town. Her mother, a midwife, statuesque, delivered her first daughter. “Velma, you have a beautiful baby girl,” she said. “What would you like to name her?” My great-great grandmother snapped back, “I don’t care. Name her anything,” so the child was named Maxine, after her father, Mack. My grandmother, Dara, tells me all this. She chops her words short and squints her eyes when she imitates Velma. Then she grows wistful. She remembers summers she stayed with her grandparents, playing in a straw house on the sandy bank of a creek that meandered behind the company town. Chiggers crawled through the straw, brilliantly red. Velma dabbed medicine on little Dara’s chigger bites with a cool glass dropper. In the evenings, Daddy Mack came home covered in coal dust. Dara ran to him, and he sent her back halfway, telling her to wait for him on the front porch swing. A few minutes later, he would come from the pumphouse, clean, damp-headed, smelling of crushed mint, and he would swing with her until dinner. Daddy Mack died in the mines when Dara was thirteen. He noticed a weak support beam one day as he went down in the mine car and sent his friends on, while he stopped to repair the beam. Somewhere above ground, Dara was practicing jumping jacks in the sun with the cheerleading squad. For years, she would keep the metal snuff can that was recovered from his breast pocket, crushed. Dara cared for Velma in her old age. She fed her, bathed her. Velma liked to see herself naked in the mirror. She looked at her aging body, angled herself the right way, and said, “I was always more like a doll than a human.” One day, she took off her ring and thrust it at Dara. Dara wasn’t sure if Velma remembered where the ring had come from, only that it should go to someone who would protect it.

Maxine, 1946. My great-grandmother wanted a canary diamond for her wedding ring. Her husband bought one for her, and she lost it, promptly, picking okra. Her replacement ring had more diamonds (but no canaries). She did a better job keeping up with her new ring. She wore it even after her husband divorced her. She simply moved the ring from her left hand to her right. All those diamonds. There was one brief period when the ring was taken from her: the time she was in the hospital. Her daughter, Dara, came home one day to find that Maxine had baked every cake in her recipe book. They were all lined up on the counter: hummingbird cake, pineapple upside-down cake, red velvet cake. Maxine was about to move on to loaf breads when the men from the hospital arrived. They diagnosed her with manic-depressive disorder, gave her electroshock therapy, broke her teeth. She never spoke about what happened in the hospital. The psychiatrist explained it to Dara in his office. Maxine said not a word. She collected her medicine, put her ring back on.

Dara, 2005. My grandmother wears a pink tourmaline ring. A large stone, rectangular. She paints her fingernails magenta to match. She bought the ring for herself on her fifty-eighth birthday. It winked at her from a shop window in San Francisco, and everyone knows: She likes pretty things. She was visiting the city with her friend Donna who had inherited a million dollars’ worth of real estate in Florida. Donna never saw the real estate. She imagined sandy lawns and bright-throated carnivorous plants, decided to let a lawyer handle it. Donna and Dara gallivanted around spending money for a few years until the lawyer found a way to funnel Donna’s money into his own bank account. Then Dara came home to Alabama, rented an apartment in the attic of a pink Victorian house. She filled magazine racks with paper dolls and set clay bowls of marbles on the coffee table. She and I sat together, when I was a teenager, and watched lightning fork across the attic skylights. She says she doesn’t miss the money. She’s glad she saw the sea lions and the Painted Ladies. Glad she bought her pink tourmaline ring.

MATERNAL

Lucille, 1979. My great-grandmother liked my mother best of all the grandchildren, so she gave her a blue glass ring. She bought the ring on impulse. There was no special occasion. Perhaps it reminded her of bluebirds, my mother’s favorite animal, or it reminded her of my mother’s blue eyes. She was traveling with my great-grandfather, Warren, in his eighteen-wheeler when she found the ring (location lost to time). It’s hard for me to imagine her in an eighteen-wheeler, though my mother says she kept a tidy mattress in the cab of the truck. I remember her with cold hands, trying to catch me as I ran through the kitchen. I remember her with the voice of a grackle. She talked about loving me, and I was afraid of her. I didn’t imagine a Lucille out of her high-backed kitchen chair. I didn’t imagine her eating egg salad sandwiches on the edge of the Grand Canyon, breathing in the juniper scrub of New Mexico. She liked to wear collared shirts with buttons and breast pockets. Sweet boyish shirts, pastel striped. I can imagine her shirts in all the places she must have been, but the shirts float empty against the landscape. I cannot imagine her.

Diane, 1964. My grandmother has fingers loaded with rings. Each ring will be inherited by one of her grandchildren. She lists her heirs for me in her kitchen, while holding a bottle of milk down to a baby goat. Behind her, on the counter, an assortment of Mason jars with raw chicken sealed inside them (torn muscle, cramped wings). In front of me, a plate of “salad” made from lime jello, Cool Whip, and pineapple tidbits. She shows me two rings with opaque stones she discovered while panning for gems in a tourist center in Georgia, a ring with three dark garnets she bought when she started driving a school bus. I remember the school bus parked at the edge of the cow pasture. My cousins and I used to run among the seats and honk the horn. The garnets have a dull glow in the sun, like the bus’s taillights. Diane’s voice goes husky when she talks about her wedding ring. She talks about her first date with Milton. He took her to the laundromat with his three children. She was smitten by his blue eyes and his curly-headed, three-year-old son. Two months later, Milton would propose. She would drop out of college, raise seven children and ten thousand chickens. Milton would buy her a washing machine but never a dryer. I remember my aunts had sore feelings about the dryer; they had years of hushed discussions around the kitchen table. I remember how strange, how mystical, it seemed to me, to watch my grandmother hang laundry on the line. And bringing the laundry back in: stiff towels and fire ants. My grandfather has been gone for twelve years now. I wonder if Diane ever remembers her years without a dryer, when she looks at her wedding ring, or if she only remembers that day at the laundromat.

Deborah, 1980. My mother received a promise ring from my father when they were in high school: a flower of rose gold with pale grape leaves wrapped around it. When my mother showed me the ring, years later, stashed in a box with spare buttons, I thought it was the most beautiful piece of jewelry I had ever seen. No one was surprised. I have so much of my father’s personality. As a high-school couple, Kirk and Deborah would not have been voted most likely to succeed. They got together, broke up, got together and broke up again. They passed each other notes with doodles of basset hounds, hot-blooded poems, calls to Christianity. They fought at prom. Finally, after graduating from high school and breaking up with Deborah for good, Kirk called from boot camp. To this day, I’m not sure if anyone knows what inspired him to propose. My grandmother was still hemming the train of my mother’s dress as she practiced walking down the aisle at the wedding rehearsal. The next day, at the altar, my father cried. He cried for the end of his childhood, which had been Alabama, cucumbers growing so fast he had to pick them twice a day, a toy chest he could hunker inside and pretend he was riding to the moon. My mother was happy to leave Alabama (to her: chicken-pecked hands, Baptist dread, tornados). She tucked away the bacchanalian rose-and-grape ring, donned a proper snowflake of diamonds. My sisters and I were raised on a plateau in Tennessee where my father studied rare salamanders. We were mostly happy. I notice: My father doesn’t mention things he misses about Alabama. My mother misses rainbows. She says in Alabama, she saw rainbows every day.

SORORAL

Emily, 2010. My older sister wears a ring with three diamonds staggered in size. She and her husband met in a high-school theater class. We were all afraid of Shaun when she brought him home because he wore fedoras and painted his fingernails black. My sister adopted his taste. We thought she had lost her mind. We thought she had been drugged, hypnotized (I swore I would never fall in love). Somewhere along the way, there was a shift in power. Today, Shaun is a history teacher; he teaches juvenile delinquents. He brings cups of coffee and slices of cake to Emily’s chair whenever she wants them. He goes out in the cold to find the knitting needle she left in the car. When he bought her wedding ring, however, my sister tells me he went “off script.” He came home from the pawn store with a ring nothing like the one she had described. A beautiful ring, my sister agrees. It’s the hardest one to photograph, it sparkles so brightly. The band of the ring is engraved with the initials and wedding day of some other couple from long ago: DJT to LRC 6/6/48. One year, my sister decided to celebrate the anniversary of DJT and LRC. On June 6th, she put on her pearls and tied a silk handkerchief over her head. For Shaun, she picked out a flat cap and a brown vest. They packed a picnic and ate beside a creek. Someone took pictures: French bread, deviled eggs, my great aunt’s tattered quilt. I wonder how they felt sitting there, dressed as other people. Could they have been happy? Every time I have had to wear a costume, my nerves have stretched until I cried.

Haley, 2015. My little sister wears a white gold ring, steppes of tiny diamonds leading up to a small meteorite of a diamond. Princess cut. I drove to Texas with her so I could sign as a witness when she eloped. Her fiancé McKenze received a two-hour pass from basic training. He asked us to take him to the mall. My sister and I walked around a fountain in the food court, trying to create an opportunity for him to slip into Zales. The air smelled of French fries and chlorine. McKenze circled the fountain with us, then ambled through the mall. He feigned an interest in a bulk package of boxers, a board game with miniature dragons and trolls. An hour later, we were back in the parking garage. My sister kept looking at me. Her eyes said, “Is this guy for real?” Suddenly, McKenze needed to go to the bathroom. He disappeared back into the mall. We sat in the car and laughed at him. The air smelled of vanilla car freshener, Texas heat. He returned, placed a bag in the trunk. After we dropped him off and he was safe behind the air force gate, he texted my sister, “I think I forgot something in the trunk.” She called him, said, “Oh really? I can’t find it,” though she was already holding the box. They were married the next day. My sister wore a white cotton dress with a quilted orange-peel pattern. I took the only photo of their real wedding (There was a fake wedding, later, with an audience). My sister is laughing, holding her hand out to block the camera. The bottom of the wedding band is white around her finger.

Mallory, 2021. I wear a thin gold ring with a diamond the size of a grain of rice. My best friend Steven gave me the ring. He wanted to put me in something more glamorous; he showed me rings with twining, multicolored stones that looked like they should belong to Elizabeth Taylor. He wasn’t surprised when I showed him the ring I wanted. This small, honest ring. We haven’t had an easy time finding a place in the world for our love: first because I was thirteen and he was nineteen, then because he was gay and I was a girl, then because I was married. Still, we had one year when we were together in our own way. A recent year, now fading. It started when Steven was in the hospital, and I flew back to Tennessee to take care of him. They had put him in a glass observation room. I held his sweating hand (to me, surreal in its beauty) and talked to him through many layers of hallucinations. He grew peaceful. He wanted to sleep. We curled up on the hospital bed, and he made me promise I wouldn’t leave. For a year after he was released from the hospital, he called me every day. We talked as I counted frog cells under a microscope for my master’s thesis. We talked as I chose Halloween cards from a Dollar Store shelf. “Get the glittery ones!” he said. When I visited him, he talked in his sleep. If I responded, he murmured, shh, and tried to sing a heavy lullaby for me. He has started dating now. He needed to. I still notice the clock every day at 4:30 PM when he used to call. Sometimes I see attractive men in the grocery store, and I feel in my gut how easily they could turn his head. I hide in the organic food section, among the wheat berries and quinoa where no one goes, and I cry. My Granny Dara says I would be better off forgetting him (She knows I can’t forget him. She has heard about Steven since I was a child beside her, waiting for the next lightning bolt to cross the skylight.) For a few months, I took off my ring. I thought taking off my ring was the strong thing to do. Then one day, while writing these words, I decided to look through my text messages with Steven. I scrolled through photos of angel-shaped cookies and tarot cards, early morning missives where I was “dearest.” I reached a photo of bergamot blooming above a sea of nettle. I remember the smell when the photo was taken: spicy and red as the flower. I had been loitering behind the other field biologists, shy to be caught taking photos when I should be carrying trout nets to the stream. I took five photos, trying to get one perfect for Steven, then ran in my rubber boots to catch up with the others. I remember running, the world green and red and alive, and my love and Steven’s love alive. Minutes later, the forest darkened under a thunderstorm. The streams swelled with rain until we couldn’t stand against the current, and we took shelter in the Forest Service trucks. Magically, through the mountains and clouds and dripping leaves, I got half a bar of cell phone service. I sent the photo to Steven. I never want to forget the feeling: the bergamot, the thunder, my little ring shining against my dull waders, my love wild and free and honest. Like so many women before me, I feel stronger when I choose to remember. I’ve put my ring back on.

Mallory Miles is an environmental biologist and creative writer from southern Appalachia. Her work can be found in Fourth Genre, Diagram, the Ex-Puritan, and The Stringybark Anthology.

A Song for Mallory